The Music of Anthony Braxton: A System of Possibilities

Essay by Carl Testa

Thumbscrew, the trio of Tomas Fujiwara, Mary Halvorson and Michael Formanek, visited the Tri-Centric archive in 2019. As the director of publishing for Tri-Centric, I had the pleasure of working with Thumbscrew to choose the scores which they would rehearse and record during their upcoming residency. It had been agreed upon that we would be looking for works which were less known and perhaps unrecorded in an effort to showcase hidden gems from the archive. Over the past 8 years in my work taking care of the archive I have been constantly amazed at the breadth and diversity of Anthony Braxton’s compositions and surprised at the number of them that have seen so few performances.

The music of composer Anthony Braxton presents a whole universe of possibilities in sound, theater, electronics, narrative, and philosophy. Braxton has referred to this composite body of work as a “Tri-Centric Thought Unit Construct Entity.” Conceptually, his music could easily go on forever, or the entirety of his composed and recorded output could be experienced as a blip of noise lasting less than a second, and everything in between. In the Introduction to Catalog of Works, Braxton lays out four fundamental postulates for the interpretation and performance of his music. These include:

I. All compositions in my music system connect together

II. All instrumental parts in my group of musics are autonomous

III. All tempos in this music state are relative (negotiable)

IV. All volume dynamics in this sound world are relative

To my knowledge, there is no other composer who has provided this level of freedom to the interpreter to impart their own identity into the performance as Braxton has.

Braxton has a term he uses called the “friendly experiencer” which is often thought of as relating to the general concept of the audience experiencing the music. However, my feeling has always been that the “friendly experiencer” encompasses the audience, musicians, and composer as one unit experiencing and creating the music together. Braxton writes in the liner notes to Six Compositions (GTM) 2001 “the system I am building (sensing) leaves room for the friendly experiencer to have a viewpoint that makes sense from that person’s own individual perspective and proclivities-having nothing to do with my disposition and/or presence...the Tri-Centric method (idea) is conceived as a system of ‘possibilities’ that can be used to facilitate agency-depending on the needs of the moment.” Braxton goes further and describes the system as “’alive’ in itself (as an entity with its own interests separate from mine) with its own agenda to fulfill.” This statement, to me, seemed to indicate that the system can keep evolving through those pursuing the investigation of Braxton’s music independently on their own terms. His music is a creative tool that any musician or listener can use to explore their own creativity and ideas in any domain.

Anthony Braxton’s Composition Notes (published by and currently available from Frog Peak) were provided to Thumbscrew for all of the early compositions that were not formally recorded as they offer key insights into the original intent and context of the compositions. The Composition Notes Volumes A-E contain detailed notes on which Braxton made for each work and include score excerpts, analyses of compositions, and descriptions of their original performance.

Below are excerpts of some of the scores that Thumbscrew recorded which can shed light on the process of interpreting Anthony Braxton scores.

Composition No. 14 score

The early Composition No. 14 is presented three times on The Anthony Braxton Project with each musician performing a version of the graphic score using their own creative logic in dialogue with Braxton’s language music system.

Composition No. 157 excerpt

Braxton writes in his Introduction to Catalog of Works that “All instrumental parts in this group of compositions are changable—that is, any instrumental part can be used by any instrument—or instruments.” This flexibility of Braxton’s music system provides an opening for Fujiwara to generate a new part for percussion from a duo originally written for reeds and bass that combines aspects of both lines into a new composite.

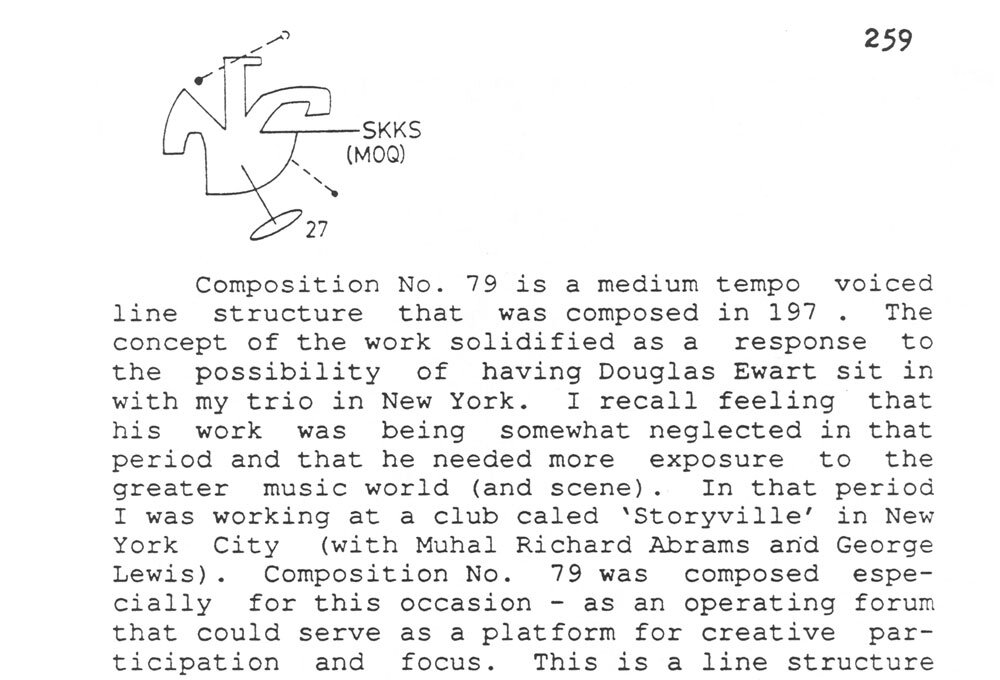

Composition Notes (excerpt) for Composition No. 79

According to the Composition Notes, the original performance of Composition No. 79 featured Braxton, trombonist George Lewis, bass clarinetist Douglas Ewart, and pianist Muhal Richard Abrams. Abrams performed a walking bass line on the piano while the three other instrumentalists improvised and performed the notated material. Braxton describes the music with musical terms such as “bebop”, “driving”, and “big-band”. For Thumbscrew’s performance they stayed true to this context with Formanek providing the walking bass line and Halvorson and Fujiwara (on vibes) performing the notated music originally performed by the brass and reeds. This composition has most likely been performed in previous contexts as “tertiary” material, notated music which basically encompasses all of Braxton’s catalog that can be collaged with other “primary” and “secondary” notated materials in a performance. In those instances, the interpreter has the decision-making agency to take the “tertiary material” and use it within the primary composition. It speaks to the notion of Braxton’s music as truly being an “erector set” that can be put together, taken apart, and put back together to suit the needs of the friendly experiencer.

While Braxton’s catalog of works now contains over 400 compositions spanning over 50 years of activity, it’s clear from Thumbscrew’s album and the work of other ensembles all over the world that we’ve only scratched the surface of what is possible within Braxton’s music. I look forward to the continued investigation into the creative possibilities opened up by Braxton’s thinking and musical oeuvre.

– Carl Testa (July 2020)

Score at top: Anthony Braxton’s Composition No. 61