James Fei INterview

I met Braxton sometime around 1995, when I got to see him in a solo concert at the Knitting Factory, but I didn’t get to really know him until I started studying at Wesleyan University. I went to Wesleyan in 1996 specifically to study with Braxton and Alvin Lucier, and they both had a profound influence on my development as a composer and musician.

At the time, Braxton was writing and performing Ghost Trance Music almost exclusively, and the music was at first frankly bewildering to me. I was drawn to Braxton’s musical universe for its broad scope and methodologies—prior to Ghost Trance Music, his output varied from those for 100 tubas, chamber ensembles, orchestras, quartet to theatrical works with constructed environments. The techniques employed and the approaches he used to integrate notation and improvisation were also continuously transforming since his first pieces in the sixties. Ghost Trance Music on the other hand, at least in its early incarnation, seemed single-mindedly focused on an unending melody. It was monumental, and indeed trance-inducing, but seemed like a complete break from Braxton’s early works.

Despite my initial reaction to Ghost Trance Music, I have been drawn deeply into its practice and evolution since 1996. At the time, Braxton was beginning to expand Ghost Trance Music to split into “quadrants,” where multiple conductors would lead sub-sections of the ensembles to play at independent tempi, or even different compositions altogether. It was a period of experimentation, where hand signals were developed to cue up different pieces, Language Music could be superimposed in various combinations, and each performance involved trying something new. It was a thrilling process to be a part of—not all experiments worked, but it was indicative of Braxton’s restless creative mind at work. From the early performances such as Composition 219/221 (available on New Braxton House), where three ensembles perform Ghost Trance Music spatially distributed around the concert hall, to the third species “accelerator whip” pieces that concluded the series, one can trace a trajectory (with many detours) that continuously redefined a musical system.

Braxton has spoken of Ghost Trance Music as a “mystical curtain,” which I understand to be a way for him to establish a body of work that was radically different than all of his previous music, so that he can come out of the other side with something new. In that light, it became clear why the early Ghost Trance Music was stripped of the all-encompassing approach he had been developing into the eighties, where all of the pieces he had written could be used in any context, often simultaneously. Now, twenty some years after he embarked on Ghost Trance Music, I can also see how it allowed him to create Echo Echo Music, Diamond Curtain Wall Music, Pine Top Aerial Music, Zim and others—these are works from the other side of the curtain. These transformative systems reflect Braxton’s perpetual efforts to push himself into new territories, and are developments that I could not foresee or understand as a 22 year-old in 1996.

Musicians often find Braxton’s music daunting to approach due to its scope and complexity, and it is challenging, but Braxton always stressed the importance of diving in and doing one’s best. Regardless of their technical abilities, Braxton often started his ensemble classes at Wesleyan with some of his most difficult music (usually Compositions No. 96 and 169). He didn’t expect the students to execute them correctly, but the struggle to do so was critical to him, and his enthusiasm for barging forward despite the imperfections is infectious. Anyone who has performed with Braxton will have experienced how he relishes the uncertainties of a challenging score (and when he’s worried about a difficult piece, he will inevitably play it faster), and how he embodies multiples rhythms and groupings in different parts of his body as he conducts—“doing the work,” regardless of challenges, is always an essential complement to the cerebral, systematic and philosophical aspects of his musical world.

My first professional gig as a musician was at the North Sea Jazz Festival in The Hague in 1997. I had been playing saxophone for only about two years and here I was at one of the busiest jazz festivals in the world, going on stage with Braxton following ICP. Despite practicing desperately, I didn’t think it was possible to be ready for the gig, but Braxton’s faith in me somehow pushed me to disregard my shortcomings and learn music I wouldn’t have thought possible. It was sink or swim—he saw something in me and wanted to see what I could do on the bandstand. Thankfully I survived the gig, and have been working with him in the following 22 years. During this time I have worked with Braxton on projects with string orchestras, a trio with bagpipes that is entirely circular breathed, premiering the piece for 100 tubas, and Sonic Genomes involving 60-80 musicians over 8-hours. What has remained consistent is his continuous push to the boundaries of his musical universe, and an unceasing enthusiasm for the discipline of music.

– James Fei interviewed by Narushi Hosoda in January 2020 for the Japanese magazine Jazz The New Chapter.

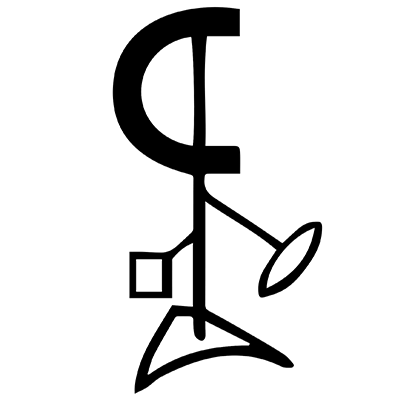

Score above: Anthony Braxton’s Composition No. 98